2024: What I Read, and How I Felt

I’ve never done one of these lists, but 2024 was an explosively productive year for me in terms of reading, and I’m grateful for it. I’ve also been lucky enough to connect with people this year who write, publish, or market books, and I feel like taking part in that entire community a little if I can. Sadly, I’m not very good at book reviews and I despise ranking lists, so instead I’m sharing a few things I read in 2024 by…feeling. Consider it an arbitrary structure to add some novelty to endless year-end lists: you can choose to explore these based on how long they’ll be with you or what they might give you. I find that some books (regardless of actual length) are long-term emotional commitments, and others are short flings. In the same vein, some are inviting beautiful, easy, approachable and delightful; others are frustrating but educational. I read all sorts this year. Here are a few.

Books I read slowly or over time; revisited frequently; on planes; in the mornings; in baths; with longing and curiosity

A Very Large Array, Jena Osman

My favorite book I read this year, by a mile. It’s so hard to explain exactly what is in this book, because it seems to have everything: reflections on the meanings of public statues, the periodic table, Walt Whitman’s dabbling in phrenology, corporate language and legal writing, all rendered into a perfectly reserved poetic experience that varies in structure every time. Discovering Osman’s writing was a revelation for me; I think what I like about this book specifically is that she is the perfect type of poet for this type of collection. She benefits from having the sheer variety of her interests and subjects and forms on display side by side. I learned so much from her writing. I’m going to keep picking up this book (gorgeously designed and printed, by the way) well into the new year and long after. If you buy one book because of this article, make it this one!

The Crack-Up, F. Scott Fitzgerald

This was technically a re-read, but I’d only ever read the titular essay, not the entire book, which is a collection of all of Fitzgerald’s last writings before his death. I am (notoriously) a Fitzgerald apologist, but even if I wasn’t, I would say The Crack-Up is worth your time as an incredible document of defeat and creative process. The scraps and fragments of writing, short stories that go nowhere, and the essay on burnout that is the heart of the book all demystify Fitzgerald in a way I don’t think even the most critical biographies can. You really see everything you need to here. Whenever I felt like a failure, I’d return to this to find traces of the story of the American dream Fitzgerald kept trying to tell, to witness the observational skills that made him a success, and to experience all the indulgent, weird, self-involved tangents that simply didn’t work. It’s healing to realize all of that talent and all of that failure can sit side by side.

Letters to a Young Poet, Rainer Maria Rilke

I read one letter a day, for a week or so, while waking up very early in the morning during the late winter. The questions the young poet had are the questions we all have; Rilke’s answers are too idiosyncratic to feel like platitudes. A classic for a reason.

Portraits: John Berger on Artists, John Berger

A massive, thick compendium of Berger on individual artists, their lives and work. I didn’t read every essay in this, but the book itself was a beloved companion to me when I lacked inspiration, or for when I wanted to meet someone new, so to speak, through Berger’s eyes. He is one of the greatest writers of art, in my opinion, not least because of how generous he is: he really wants to tell you about why these artists are worth your time, and about what makes them interesting. His essay on Caravaggio is a favorite.

America, Jean Baudrillard

I read this for the first time and also reread Adorno’s Minima Moralia this year as background reading for a larger project, which was a wild ride. I love Adorno, but I think that whatever I wanted out of Minima Moralia I got out of this, but better…not to pit two queens against each other or anything, it’s just that Baudrillard’s writing is so pleasurable to read. The style with which he traverses America, making comment on Los Angeles, highways, television, and casting a sort of ominous clarity on the culture’s various contradictions, is…well, it’s very 80s and very French and very much my type of shit. But unlike some other offerings in this niche, not every observation is definitive or even analytical. Long stretches are simply description, with the ideas broiling underneath:

“All around, the tinted glass facades of the buildings are like faces: frosted surfaces. It is as though there were no one inside the buildings, as if there were no one behind the faces. And there really is no one. This is what the ideal city is like.”

I just think that’s such a fantastic way to write. I want to write like this someday. I tried to write like this this year, a little bit. Anyways, America is great. Read that and Minima Moralia for a double feature in ‘25, if you dare.

Kairos, Jenny Erpenbeck

What can be said about it that hasn’t been said already? I adored it immediately; the beginning of the novel beautifully captures the phase of falling in love where the shape of your desire becomes a vessel into which everything else is poured, where the world becomes sharper because of your desire, where everything you do is bent around that person, a new center of gravity. Reading Kairos made me realize how little I knew about 20th century German history after World War II, and how valuable it is, actually, to go in relatively blind to such a heavy and complex subject and experience it through the eyes of these characters. Not to defend ignorance, of course; it’s more that I didn’t really have a sense of any direct cultural experiences or details of the East-West split, the fall of the Berlin wall, etc. I do now, and I also have those characters living in my head. What wonderful writing. What a wonderful book.

Books read quickly while sitting still; all at once; with total attention; hungrily; with focus

Greasepaint, Hannah Levene

The blurb on the back of this novel, from independent publisher Nightboat Books, says that Levene studies something called New Butch Literature. Well, if that exists, Greasepaint is certainly “it.” I’m perhaps biased because of my time spent amongst the elder butches & dykes of Buffalo; there’s a photo somewhere of me in a little yellow minidress, standing with a microphone surrounded by grey-haired lesbians, who are reading portions of Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold, Madeline Davis & Liz Kennedy’s canonical oral history of Buffalo’s lesbian bar scene. Boots of Leather takes place in the same period of time as Greasepaint, but Greasepaint happens in New York, in the niche communities of anarchist Jews and jazz pianists and working class scrubs and whoever else could make it to a bar in the 50s. I’m impressed by it, deeply, because it pulls the niche-ness off without ever feeling precious or preachy. The style is a direct, cascading flow of dialogue, but the characters are anything but one-note, and refuse to explain themselves, bearing out all their internal dynamics and flaws as people really do in real life. It’s been a long time since a lesbian novel excited me as much as this one, perhaps because it doesn’t apologize for itself or explain what lesbianism is. It simply is; the concerns of the novel are what happens next.

Baumgartner, Paul Auster

I'm so sad we lost Auster this year. His writing rearranged a few crucial building blocks in my brain when I was young. Among other things I think he’s a master of open endings that don’t feel like open endings, and he’s very good at intense forward motion. Even when he wasn’t writing novels influenced by mystery or crime genres, that hectic, obsessive energy (so much like a detective tracing footprints) seems to be present, and it’s present in Baumgartner, which is really a story about loss and aging and memory, about a man rebuilding his life after losing his beloved partner. I originally meant to read this one in 2023 right when it was published, but that same month I finished Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and I decided that I had to space out the "my wife is dead" books by at least a few months. I’m glad I didn’t forget to read it this year. It was a great read for mid-spring, a love story that trembles in the confusing space between vitality and fragility and then barrels forward into the unknown.

Agapë Apage, William Gaddis

I read this in one sitting in a hotel room in San Francisco this February, during the two hours I had before I was due to attend a concert at a venue around the corner. All alone in the city after a long workweek, with that weird pre-show anticipation in my stomach, the novel, as they say, “hit different.” I was familiar with Gaddis, but had only read Carpenter’s Gothic before picking this up on a whim after seeing Hal Foster mention it in his most recent essay collection. (That one is called What Comes After Farce, and was fine, but didn’t make the list. Sorry Hal.)

Structure-wise, Agapë Agape is very different than anything else Gaddis ever wrote. It was released posthumously in 2002 and is one long run of dialogue from a dying man who is attempting to bring his feelings on contemporary culture to bear in the face of his own mortality, a struggle told through his research into the social history of the player piano. If you, oh, I don’t know, are fascinated by the symbols that surround us, want to reflect on how romanticizing the past comes with a built-in death drive, or have trouble reconciling the horrors of modernity with transcendental experiences of live music…give it a read, maybe, on New Year’s day.

Suite Vénitienne, Sophie Calle

Sometime in the late 80s, the artist Sophie Calle arrived in Venice with the singular mission of finding, following, and photographing a man who she referred to as Henri B. Her well-documented investigation into Henri B.’s whereabouts, as well as her photographs of Venice and B. (as she eventually discovers him) comprise the piece Suite Vénitienne, which you can read easily in one sitting. It is one of my favorite pieces of art about desire, process, and public space, partially because it does not come with any great revelations or any satisfactory conclusions. It gives me many ideas for stories I’d like to write. Worth anyone’s time.

Books read with productive frustration; thrown across the room; put down and picked back up; enjoyed; learned from

Lobster, Guillaume Lecasble

Did I like this novella about a lobster aboard the Titanic and his erotic relationship with a near-suicidal woman who survives the wreck? I literally could not tell you. But I read every word of it, on the recommendation of an acquaintance who works in perfume, because this is undeniably a scent-driven story. It’s also so painfully French that I felt dirtier reading it in translation than I did reading about a shellfish perform oral sex. I think it’s interesting as a story that manages to be gross in completely new ways, all while perfumed with the scent of a bay leaf.

Boss Broad, Megan Volpert

When Megan Volpert (who I now know in person, and who is super cool) starts in on an analysis of the TV show Broad City in her book Boss Broad, my immediate, post-2016 millennial reaction was to fling the volume across the room and hide, as if any proximity to its reputation of pop-feminist cringe would taint me. But well, that’s no way to live your life, is it? I’m all the better for continuing my read, because Megan is smart as hell and Broad City, whether we like it or not, happened. Besides, the book isn’t really about that. It’s about Bruce Springsteen, exploring his mythos, loving his music, and being a woman while you do it–all topics I care deeply about. Once I got over myself and let the author’s voice drown out my inner cynic, I loved her conclusions and explorations, which are bluntly honest and intensely personal. I’m also glad at least one other person on earth finds Stephen Colbert as symbolically fascinating as I do. Check out her writing on perfume, too, if you get a chance.

You Are the Snake, Juliet Escoria

I have trouble with contemporary literary fiction; I have trouble buying into it and letting it take over and absorb me; I have trouble believing it’ll take me anywhere good. I don’t even remember why I picked up an ebook of You Are the Snake, but I’m glad I gave it a chance. There’s a story in this collection which is so masterfully horrifying in its understated depiction of suburban trauma that I was too freaked out to finish the book for weeks after, and I’m going to say that’s a compliment in this case. Lots of gray area, lots of vivid, bad, cruel characters, and lots of questions about why people do the things they do. I liked it a lot.

Nomenclature, Dionne Brand

My first exposure to Dionne Brand was via a longform podcast interview she gave this year, in anticipation of her new book Salvages, which I own but haven’t read yet. I found her entire approach to poetry and politics refreshing, but Nomenclature is not about feeling refreshed. Brand is an unflinching communist, and an unflinching poet. Smarter people than me have said that. But I think we all wonder a lot these days about political writing and how to do it, how much to do, and above all how to prevent political art from being sucked back up into the commercial systems that weaken politics. No answers from me on if Dionne Brand has hacked that, but I think the sheer scale of this poetry collection, and the way Brand can go from intimate to starkly descriptive in seconds, gives me hope that maybe the answer is yes. She is a beautiful read, but not an easy one, and thank goodness for that. I’ve read huge sections of this book and still feel like I’m only scratching the surface. She’s so awesome. Read her poems!

Cranked Up Really High: Genre Theory and Punk Rock, Stewart Home

I first encountered Stewart Home’s writings in my 20s: he wrote about Lettrisme, the Situationist International’s strategies, and all kinds of other less-researched topics in the history of radical art. Home is, to put it lightly, a distinctive personality, and Cranked Up Really High, his book on punk rock, is emblematic of his specific brand of crazy. It’s one long refusal of punk’s coveted spot in the academic genealogy of the avant-garde, from someone who was there, but also from someone who is pissed off at the way the label of “radical” smoothes over art’s rough edges. That’s of interest to me lately; the way that everything that has value or was antagonistic has to be inherently leftist is a classic academic solipsism that avoids the hard work. Still, this is in the “fun but frustrating” section because home’s writing is sort of intentionally abrasive and wild:

“Much to my delight, “Cranked Up Really High” succeeded in getting up the noses of anally-retentive record collector scum, who now have to suffer my scorn alongside that of various individuals responsible for bootlegging ultra-rare super-dumb sleaze-bag thud from the late seventies and early eighties. That’s punk for you punk, if you ain’t up for slagging the things you dig most, then you just don’t have the necessary ATTITUDE!”

I mean, there you have it. The book’s style is singular, and often reads as a parody of rock journalism, swinging between the fetishistic “I was there” storytelling to scathing bluntness. I love it; Home is one of those writers who I’m glad exists–I think his next project is about yoga and fascism, and I’m going to tune in, probably.

Beautiful books; books I am glad to own; books that are visual or tactile

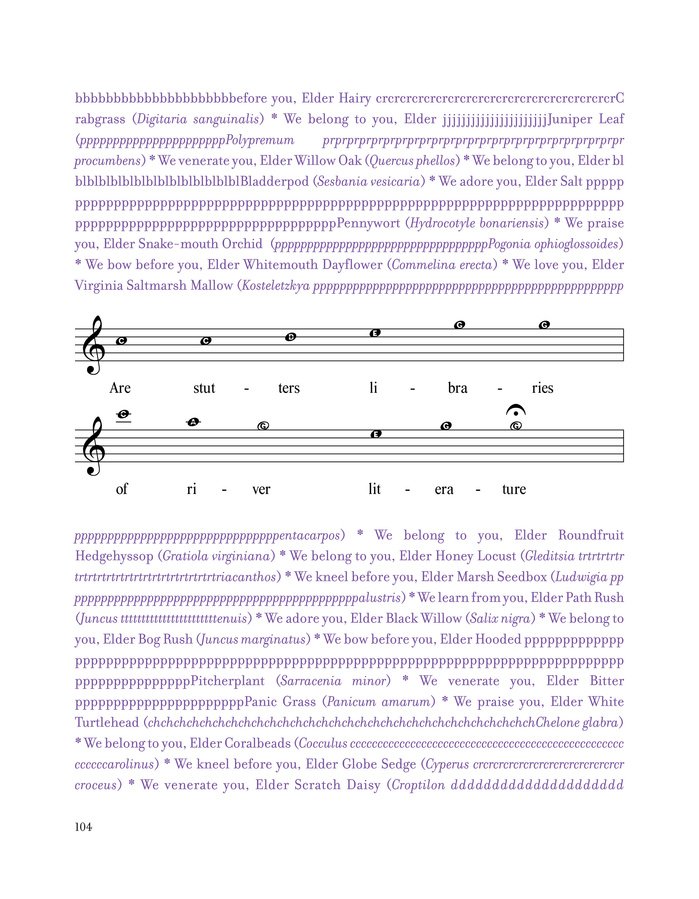

Aster of Ceremonies, JJJJJerome Ellis

A lot of “theory writing” these days is based on watered-down versions of complex philosophies of language and the body, of semiotics and the self. One of the terms that gets garbled in and applied to bad artist’s statements is “speech,” that thing that constitutes reality and happens between people, that thing that can be an act or a motion but is, rarely, the thing that you actually do with your mouth. But Aster of Ceremonies is about speech as such, and about the physical limitations that can impede it, and by extension all of our relationship to the sound, ourselves, the world. JJJJJerome Ellis’ chosen name is a reference, among other things, to his stutter and speech impediment. It shapes his identity, literally:

“My name, in the time when I cannot utter it, maps the space within me. In an instant the Stutter shuttles me from the present–the barber just asked me my name, my voice fluttering in my throat, struggling not to tremble as the razor presses on my temples–to an ancient place of breath, name silence time creation.”

In Aster of Ceremonies, Ellis creates entire visual scores and rituals around speech and speaking. There is sheet music. There are pressed flowers. It all leaps off the page in vivid, magenta ink. It’s now on my bucket list to attend an artist talk or performance of Ellis’, because this book is a true work of art–buy a copy before it goes out of print.

Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines Catalog, Brooklyn Museum

I don’t buy a lot of museum catalogs the same day I see exhibitions, but this one was worth it. I really liked what this exhibition had on offer regarding zines and zine history; the only thing I felt I wanted more of was a tactile experience, and the book sufficed at least a bit with its excellent reproductions of so many of the zines included. I’ve brought this book to at least one zine DIY night so that folks who are new to the medium could get a bird’s eye view of its history. For that reason alone, it’s an excellent purchase and a great publication, because I don’t think something at such a high production value existed until now. The essays are decent too, though nothing brand-new, but I don’t think zine culture needs to be theorized into the ground: just recorded, cared for, and made as publicly available as possible.

Unlicensed: Bootlegging as Creative Practice, Ben Schwartz

God, this book is hot. I’ll admit it: I bought it because of how it looked, even though Schwartz’s interview with Experimental Jetset was relevant to my research. It’s all-black, with images inverted to avoid copyright violation, and the print and layout is just delicious. I think it’s smart that this is an interviews project rather than just a theory of, as the title implies ,“Bootlegging as Creative Practice,” which sets off alarm bells in my head for the kind of un-substantive academic design theory all my friends pass around rude memes about on Instagram. But I was pleasantly surprised by the theoretical underpinnings, where they appeared: Schwartz is interested in the “dark matter” model of cultural excess, and discusses bootlegs in those terms, not exclusively as radical art or détournement. I think this is very smart and 100% the correct approach; it’s impossible to say that copies are “radical” just for being copies, because despite the oppressive regime of copyright law that exists in Western society, excess is still excess, and not everything means something. There’s good research here, I truly like the writing, I love the layout–long story short, I’m glad I own this book. Also, a viral joke I made on my tumblr account back in 2014 comparing Lindsay Lohan to Bernini’s statue of the ecstasy of St. Theresa made it into the introduction, which is probably the closest I’ll ever get to being published, so I’m biased.